Open-grain vs. closed-grain wood – FineWoodworking

What is the difference between open- and closed-grain wood? Understanding wood at a cellular level is not necessary for woodworking, but I find the knowledge gives me an extra tool in my arsenal. Having a deeper relationship with the material I work with has an impact on how I select and use it, and can drastically change the final product. Wood selection goes beyond just color; since furniture is an interactive experience, using different species to make creative choices in texture can change the look and feel of a piece entirely. In some applications, there are things like gluing and finishing that dictate what species to use. Open- and closed-grain wood is just one of the many distinctions you can make between species, and is a good example of the importance of selecting proper material for a project.

Under the surface

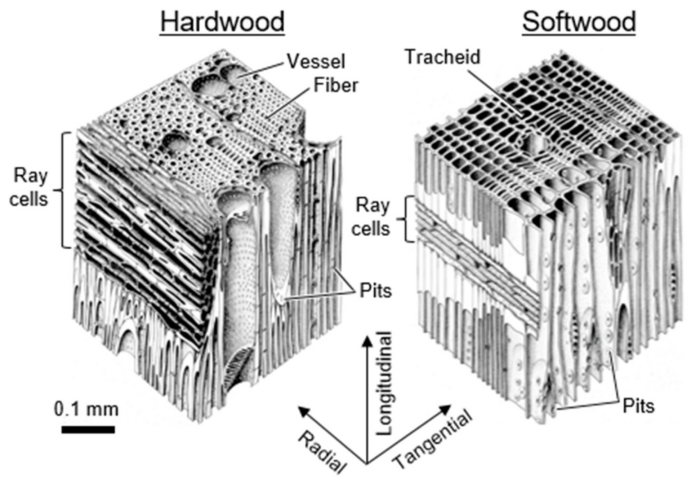

All wood species break down similarly at a cellular level, the distinction is found between how different types of cells are distributed through the wood. I often compare wood grain makeup to a bunch of straws. A tree requires pathways that supply nutrients to the leaves and branches; these run through the trunk and limbs. What the majority of woodworkers utilize, especially with kiln-dried wood, is the trunk of the tree. The difference between softwood and hardwood can be deciphered by examining the makeup of cells.

Softwood, or coniferous woods, have cells called tracheids. These act as conductors for nutrients supplied to the tree. Individual tracheids are usually visible under a magnifying lens; to the naked eye they appear as varying textures. What we consider open and closed grain has mostly to do with texture. Larger pores are more common in earlywood, which is made up of the growth made early in the season. Larger, thin-walled tracheids supply more nutrients to the tree during this season. Later in the season, tracheids become smaller while walls become thicker and more dense, providing strength and rigidity to the tree when the weather turns colder.

Earlywood and latewood can be differentiated as growth rings in a cross section of the tree. Resin canals, or resin ducts, are unique to softwood and more prominent in species like pine. The majority of softwoods can be considered closed-grain wood, since tracheids are only 20-60 micrometers wide in most species.

Hardwood has a wider variation of cells, including vessel elements, which are larger conductors with thin walls. These are unique because the cells are open from end to end, unlike tracheids, which are closed. The vessel elements are visible to the naked eye and appear on cross sections, or the end grain, of wood. These open-ended cells are called pores. By this terminology, hardwoods and softwoods are porous and nonporous woods. Since hardwoods contain both large concentrations of these large and small pores, they are more often considered open-grain wood. Fibers surround these cells and provide rigidity.

Ray cells can be seen from the face of the wood, as they run from the center of the tree outward. These conductors are thin walled and can be fragile and create large open pores. The last type of cell that is important in identifying closed- and open-grain woods are tylose: bubblelike cells that sit between early and late wood and block vessel conductivity. These are more prominent and visible in certain species, such as white oak.

What we can see

Open- and closed-grain woods are generally categorized by what we can see with the naked eye. Cellular makeup can help further identify these woods and understand what you see. Visible pores are found on open-grain wood like oak, ash, and hickory. Closed-grain woods such as maple, walnut, and cherry have pores that are not visible to the naked eye.

When to use open- or closed-grain woods

These differences are important when it comes to choosing wood for a specific use. For most furniture makers, aesthetics are the primary reason to select open- vs. closed-grain woods. But there are several practical applications as well. The high quantity of tylose cells in white oak prevents water passage, making it ideal for things like whiskey barrels. Woods with a concentration of pores in earlywood make wood easy to split for basket making. A more even distribution of pores with the same size make a wood ideal for carving. Many flooring applications wear differently over time due to the change in cell wall thickness.

It is also important to consider the wood’s texture when using adhesives and finishes. Pine may finish unevenly due to resin canals and the change in density between earlywood and latewood. Open-grain woods may need a wash of diluted glue before the final glue-up to achieve a non-porous adhesion surface. I recently chose beech wood, a closed-grain wood, for a project that would be exposed to moisture and paint often. Closed-grain wood is also ideal for food-safe cutting boards and utensils. There are many ways to work with and around these factors, but anticipating the potential issues and using species that work in our favor can be just as important as choosing correct joinery.

|

Determining grain directionRules of Thumb: Understanding wood grain improves your success with hand and power tools |

|

All about wood scienceTo quote R. Bruce Hoadley, “Wood comes from trees. This is the most important fact to remember in understanding the nature of wood.” |

|

Tips for finding the best grain in a boardMason McBrien’s tips will help any woodworker get the most out of their lumber stash–without sacrificing beautiful grain selection. |

Sign up for eletters today and get the latest techniques and how-to from Fine Woodworking, plus special offers.