Aniekan Udofia – You Think You Know, But You Don’t

Stand in any metropolitan corridor and ask the art scene denizens there what they know about Aniekan Udofia. Some might list the 33-year-old among his generation’s most talented visual artists, with national attention on his work in hip-hop magazines such as XXL, Vibe, and The Source.

And on a local level, others might even christen the Nigerian artist as “the face of the D.C. art movement that mixes political themes with a hip-hop aesthetic.” But no matter what you hear, Aniekan will tell you himself they only scratch the surface of who he is.

For starters, meet his parents, Dr. George, and Edna Udofia. They came to the U.S. from Nigeria for school while Civil War raged back in their home country (the Nigeria-Biafra War lasted from July 6, 1967, to Jan. 15, 1970). Nigerians first came to the United States to attend American universities, intending to return home, writes Kalu Ogbaa in his book “The Nigerian Americans.”

But for the first time in Nigeria’s history, the civil war “became the cause of immigration, and more students from the war-ravaged Eastern Nigeria easily made good cases for their immigration to the United States.” So George and Edna studied law and nursing, respectively, at universities in Washington, D.C. They settled down and started a family. Aniekan, the second of five children and the first son in the family was born on Nov. 26, 1975.

Ogbaa, professor of English and Africana Studies at Southern Connecticut State University, continues: “The gloomy sociopolitical and economic conditions in Nigeria resulting from their civil war were so unbearable for Easterners that everybody wanted to flee the country.” By 1980, the number of Nigerian immigrants in the U.S. rose to 25,528.

In addition, the emergence of military dictatorships, the abuse of power, and the denial of human rights also led to a mass exodus of trained personnel in university institutions from Nigeria. By 1990, the number of Nigerians in the U.S. doubled to 55,350. But instead of following the trend, George and Edna decided to whisk their children away from their birthplace in Northwest D.C. to Nigeria’s Akwa Ibom state in 1982.

Aniekan, who was 7 at the time of the trip, is of the Ibibio people, one of more than 250 ethnic groups in Nigeria – the three most popular being Yoruba, Ibo (or Igbo), and Hausa-Fulani. Located in southeastern Nigeria, mainly in the Cross River state, the Ibibio are rainforest cultivators of yams, taro, and cassava. They export mostly palm oil and kernels and are noted for their skillful wood carving.

Back in Nigeria, George taught French in high school, and Edna was a health educator. They had high hopes for their first son, Aniekan. “As a patriarchal society, sons are trained to be strong and assertive and to develop leadership qualities that will enable them to inherit the leadership roles of their fathers at home, should such fathers die or become old, ill, or infirm,” Ogbaa writes.

In addition, “They are supposed to be providers of their family member’s needs and to give them security as well as emotional and economic protection at all times.” According to Aniekan, his parents thought he was destined to go to college and major in something more practical than art, or pick up a trade and work with his hands. But instead, he embraced a movement from overseas.

Having grown up on highlife, a musical genre that originated in Ghana in the 1900s before eventually spreading to Sierra Leone, Nigeria, and other West African countries by 1920, Aniekan was familiar with legends such as Ibo highlife innovator Sonny Okosun and Victor Olaiya, a Yoruba singer and trumpeter. But hip hop captured the then-17-year-old in ways highlife couldn’t. “It was the expression of it…Even with Slick Rick, how he tells the story,”

Aniekan recalls. “He’s rapping, but it’s like he’s singing…the art of twisting words.” (He likened listening to Kool G Rap, a precise wordsmith, to “playing Tetris at high-speed.”) Aniekan’s first encounter with the art form was through a friend, who passed him a Kid ‘N Play cassette tape in 1992.

Other encounters came through friends who got VHS tapes of Yo! MTV Raps from their relatives in the U.S. “We didn’t have a VCR,” Aniekan says. “It was like one person in the hood had one, so we would all go 15 deep to that person’s crib, hang out, watch those videos, and get all hype, trying to talk like the guys in the videos.”

At the same time, record shops started popping up all over Uyo, a city that became the capital of Akwa Ibom State on Sept. 23, 1987. “You had DJs who had spots like that and they put these big speakers outside,” Aniekan says. “That’s where we used to hang out.” Other hang-outs were barbershops, which usually consisted of a closet-sized space with a chair, a sign, a comb, and some clippers.

Some barbers were fortunate enough to turn their humble beginnings into a franchise. One such barber was “Big Stuff,” who had three shops in commercial areas throughout Uyo.

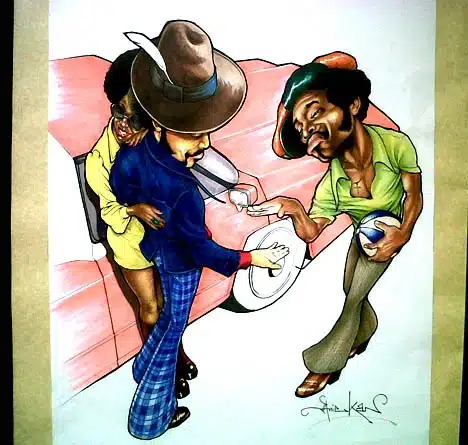

At the time, it was customary for barbers to commission local artists to create price lists and posters for their shops. Big Stuff commissioned an artist that completely changed Aniekan’s life. Through this artist, the budding hip-hop head would understand the power of expression through illustrations. “It was a guy named Arabian…He would do shit and you would just look at the piece [amazed],” Aniekan says. “He had a lot of creativity.”

He recalls Arabian incorporating hip-hop styles, with guys dressed in hoodies and posing in the stylish rides of the time. “The style was so crazy the way he did it. Every last one he did was different.” There was a price list, where a guy had a finger over his mouth while another hand pointed to a price list painted in what looked like a hole in the wall.

Another one was an illustration of three guys posted up outside a well – one guy on a cell phone, the other on look-out while the third pulled a price list out of the well. “His imagination was just something crazy,” Aniekan says. “Crazy!”

However, his hopes of finding a mentor in Arabian were dashed when they met in 1995. Until that point, Aniekan would walk around with a sketchbook, looking for work that Arabian illustrated. “I would go try to copy it and practice at home,” Aniekan says.

Noticing the young artist’s interest, Big Stuff gave Aniekan an Arabian piece from his shop to take home and study. “So I went and studied it and tried to figure out how he used the color, what kind of color he was using.” (“Was it watercolor or crayons?” he wondered). This was between 1994 and 1997, what he called his “study era.”

It’s the era he practiced the “photo-realistic” style of drawing. He experimented until he came up with his style of drawing faces with colored pencils and ink, and then pasting them over a different background.

He was anxious when Big Stuff took him to Arabian’s home in 1995. “When I finally met him, I was all groupie-fied,” Aniekan says. “I get to meet him and I’m all shy.” The magic soon wore off, when Aniekan said Arabian had promised to draw him something. “He never really got around to it. It just turned into me constantly going over there and him blowing me off.”

He turned that discouragement into determination and set out on a one-man mission to figure out how Arabian did it. In the process, Aniekan slowly made a name for himself by drawing various haircut styles and selling them to barbers. He started coming up with his concepts for barbershop posters.

In an earlier creation, he took a piece of board and drew a hand-cutting hair with an arrow pointing toward the barber’s chair. “People would see it from down the hill and they would know a barber was right there,” Aniekan recalls. In exchange, the barber gave him $50 for the poster. Aniekan aimed to get his name, like Arabian’s, all over Uyo. He soon became a sought-after artist among local barbers asking him, “Yo, could you draw me some haircuts or whatever.”

His popularity, however, wasn’t enough to impress his parents, nor quell their desires for him to fulfill his duties as first son. “I went to technical schools [and] vocational schools; they were trying to change my mind,” Aniekan says. But everywhere he went, he saw people as passionate about their fields as he was about art. During the 17-year battle with his parents, he wrote letters to an aunt that lives in D.C. After several correspondences, she granted his request by sending him a plane ticket to come and try his hand at the U.S. art industry.

He came to D.C. in 1999, at the age of 24. Since he’s been here, he’s captured the national attention of clothing designers and magazines – no longer the new fish splashing around in the national art scene. He’s created designs for And 1, an urban athletic wear company, and was the premiere artist for the D.C.-based Native Tongue Urban Apparel line.

In addition, his works have been featured in various urban publications such as Rime, Elemental, DC Pulse, and Frank 151. His illustrations also graced the album covers of hip-hop artists such as Critically Acclaimed and Flex Mathew, as well as the covers of books and hip-hop journals.

In 2004, Aniekan joined Artwork Mbilashaka (AM) Radio, a loose band of four to 10 visual artists and a DJ. They’re contracted by corporate clients to create a 7 x 5 artistic interpretation of their logo in front of a live audience. As a part of this group, Aniekan worked on projects for clients including Red Bull, Heineken, Honda, Current TV, Timberland, and Adidas.

He uses hip-hop themes as social commentary on issues he feels are left lingering such as religion, gender wars (“Is homosexuality right or wrong? Who’s to choose?”), and racism. They also focus on American consumerism. In one of his controversial pieces, former President George W. Bush is in several poses, holding machine guns. On his shirt: “Got Oil?”

Some of his work was controversial enough to draw criticism from viewers, and some galleries have even asked him to take down his paintings. Even still, his style of “telling the truth” is one most people can appreciate.

In a June editorial review, Rhome Anderson (DJ Stylus) likened Aniekan to a local treasure. “From murals around town to his live improvised painting at musical events, Udofia is as much a fixture in the urban art scene as the DJs, vocalists, producers, and musicians,” Anderson writes on washingtonpost.com. “As part of the Words, Beats and Life’s ‘Remixing the Art of Social Change’ teach-in, Udofia was commissioned to craft a completely new series of pieces.”

On a Tuesday afternoon, Aniekan is hard at work on a new commission. His one-room apartment on 17th Street NW doubles as his warehouse and art studio. Cross the threshold and you walk towards a stash of comic books neatly stacked alongside various hip-hop and art magazines. Look around, and you’ll see a work-in-progress set on an easel in the middle of his kitchen – artwork lining the wall along the entrance, above his cabinets, and into his bedroom.

His most recent show, The Sickness 3, opened at Dissident Display on H Street NE in June. Aniekan wanted the show to be a departure from his popular hip-hop-themed works. His peers’ reactions varied. “It was good and bad. Some people were like, ‘I’m not feeling this new, monochromatic, one-color-themed, crazy stuff,'” he recalls. “But then there were people who were like, ‘Wow! That’s dope.’ It’s a stretch and I feel I need to tend more towards that side.”

Looking around his kitchen, a reporter noticed a photo of Fela Kuti, the Nigerian multi-instrumentalist musician and composer. In the artwork, three different Felas take on different hues – a blue Fela looks up at a black and white Fela who’s playing the saxophone. In the background, a silver Fela raises his arms in a victory pose through an outline of Africa.

When asked if Nigeria or elements of his Ibibio tribe ever work their way into his paintings, Aniekan looks up from a sketch to carefully consider his answer. “If I choose to do a specific back home kind of theme”-such as the EVOLUTION OF CULTURE show, which opened April 3 at Wisconsin Overlook on Wisconsin Avenue NW- “that’s when I usually bring out those traits of where I’m from,” Aniekan says. “It’s more of a choice.”

It’s a choice he feels that musicians and other artists should have the right to exercise without being labeled cultural sell-outs, or worst. Take Fela, the Afrobeat music pioneer, and human rights activist. He didn’t start as the political maverick he’s known as today. “He was into music…he started with highlife, which he grew up into,” Aniekan says.

When Fela noticed some social and economic issues went unaddressed, his music became his bullhorn – “where he started just banging on the presidents” and corrupt politicians. “That took him to another level,” Aniekan says. “He wasn’t writing just about Nigeria; what he wrote was pretty much Africa, itself, and the world.”

That connection with the world is what Aniekan is looking for with his art. He knows If he puts his art in a box labeled “African art,” it would narrow the scope of his work. The same thing if he only did “hip hop” paintings. So what does he do? He pushes himself with each image. Aniekan says, “As a visual artist, it’s for people to see your progression.”