On learning Khatam: The art and craft of Persian woodworking

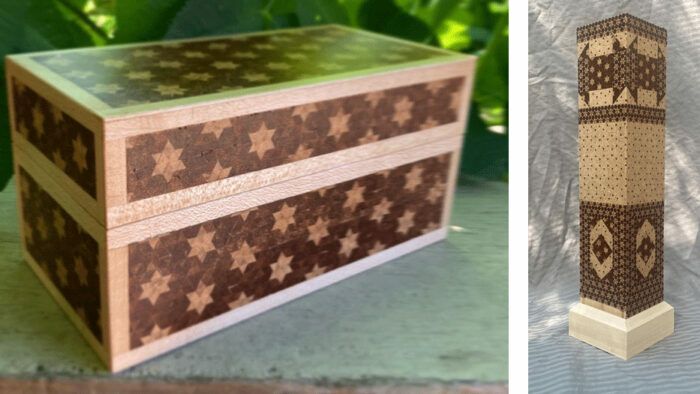

Khatam is a woodworking technique that has been practiced in Iran since at least the 14th century, and probably long before that. It is one of Iran’s most important crafts, but there are few practitioners outside the country. To make khatam, tiny triangles are combined to create complex geometric patterns in the form of veneers.

These small triangles have sides that are usually 3mm or less and are made of various wood species, bone, and metal. The veneers are used to decorate a wide variety of objects from the every day to the sacred, from backgammon boards and pen cases to the tombs of Sufi saints such as that of Shah Nematollah Vali in Mahan, Iran.

My interest in khatam springs from the combination of two passions – craft and spirituality. When I converted to Islam, I had already been a woodworker for a decade and naturally became interested in learning about woodworking traditions from the Muslim world. I discovered khatam while researching Persian woodworking and was drawn to the beauty of the patterns and the precision required to work at such a small scale.

Finding information about khatam in English is surprisingly difficult. This is in part because, although people all over the world make things out of wood, woodworking literature in the West focuses almost exclusively on traditions from Europe, North America (and there almost only that of the descendants of European settlers), and Japan.

I was only able to find three useful English articles on khatam: one by a British conservation student who studied in Iran, and two histories that were translated from Farsi, the most commonly spoken language in Iran. There are, however, multiple YouTube videos by khatam makers showing important details, such as the unique process of gluing the sticks together using string instead of clamps.

Many khatam makers from Iran are also active on Instagram. Although this information is almost all in Farsi, I learned the basic techniques by applying my woodworking experience to what I saw in the videos. In this way, I learned without knowing Farsi, which I think points to woodworking as a powerful medium for communication across cultural and linguistic barriers.

This two-part video series highlights the steps of making khatam.

After a couple of years working on khatam in my spare time, I was awarded the Museum for Art in Wood’s Winter Residency for 2023. I spent two months diving deeper into research and refining my khatam technique. The museum, located in Philadelphia, facilitated meetings with other artists and woodworkers, as well as curators and conservators from other institutions.

I made more progress on the khatam technique than I had in the previous two years. The residency culminated in an exhibit and a talk on my work. Having improved on shaping the sticks and gluing them accurately in my residency, I’m hoping to build on those skills by incorporating bone and brass into my patterns in the future.

While doing research for the residency, I reached out to an Iranian khatam maker on Instagram, but we lost touch when the protests erupted in the wake of the murder of Mahsa Amini and the Iranian government shut down much of the country’s internet. I then reached out to another khatam maker who studied in Isfahan, one of the major centers for khatam in Iran.

What began as a halting conversation between two woodworkers using sometimes inaccurate online translation apps became a friendship as we shared about our families and exchanged pictures of what each season looks like in our homes. I also started to teach myself Farsi, both because I needed it to do my research, and to be respectful of the Iranian makers who were helping me.

While these personal connections are small in scale, I think they offer lessons that can have a bigger impact. For instance, khatam has a long, rich history, but what little information is available in English is difficult to find. It is important to be aware of how our field privileges European woodworking.

This isn’t to say that everyone needs to start learning about non-Western craft traditions. But we should at least notice that we haven’t been paying them enough attention. In addition, it is important to recognize that what we choose to make has social impacts beyond the physical objects we produce.

For instance: by communicating with Iranian khatam makers and seeing how they were being impacted by the sanctions imposed by both our government and the Iranian government, I became more aware of the political situation in Iran and how it affects people in their day-to-day lives. This is important because Americans and Iranians need to recognize our shared humanity.

I’ve also included some of the accounts I interacted with during my studies:

@kazmi.khatam: the maker from Isfahan whom I communicated with the most

@majid.ghashghae: another maker from Isfahan with whom I exchanged a few messages

@norooz.gallery: a woman-owned gallery in Isfahan that specializes in khatam

@arash_golriz_khatami: a multi-generation family of khatam makers. Their Instagram posts have a lot of information about the history of khatam and important khatam makers from the past.

Michael Ferris is a furniture maker based out of Philadelphia. His work can be found on Instagram at @ferrin.woodworking

Sign up for eletters today and get the latest techniques and how-to from Fine Woodworking, plus special offers.