Going Pro: Part 1 – FineWoodworking

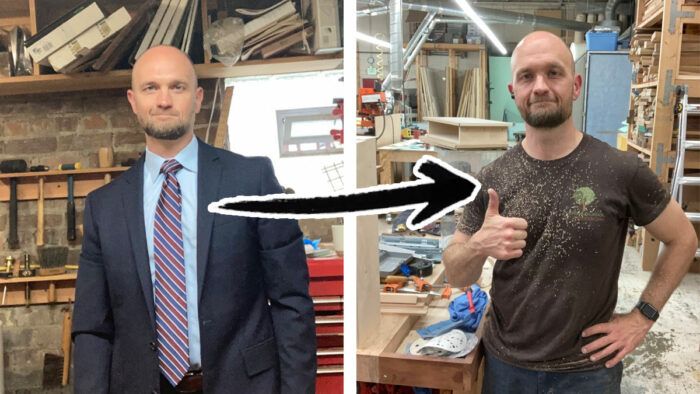

We all know the old saws: how do you make $1 million dollars in woodworking? Start with $2 million! (HAR HAR) It’s no secret that it is a very hard way to make a living, and even some of the best people in the craft will tell you how they have struggled and perhaps advise you to keep it as a serious “hobby”. So why do so many woodworkers daydream about it, and why do people like me try it?

The basic reason I decided to go pro in woodworking was simply that I couldn’t not try to do it. I could not stop thinking about woodworking: what I would build next, different business models for it, etc. When we went on vacation, I would seek out wood-related things: museums, shops, trees, etc. I was reading David Pye before work and watching The Woodwhisperer at night after dinner.

This is probably true for a lot of people who are passionate about something. Many, perhaps wisely, keep it as a hobby: they make whatever they want, mostly for fun, for friends, or family. Others will make things and sell them on the side (which is technically doing it professionally); but they are not relying on the income, or have another, primary income source. I, however, am one of those people who saw the ultimate expression of this craft in being a “pro.” It was not a business decision; it was an emotional decision, but also one of those things that felt inevitable. Once I started walking in that direction, I wasn’t going to turn around. It was the destination.

Financially, for me, the best option would have been the middle road: make commissions and small items and keep my federal government job. I had a good position, lived pretty close to work, and had a nice home shop. When I had to work overtime or was away from the shop for travel or long hours, I used my extra money to buy new tools. It was a good balance. Until it wasn’t.

As I matured in my office job, I became more efficient. I came home with more energy and could usually manage to get everything done in the allotted 8-hour workday. I had more energy, time, and attention that I could increasingly focus on woodworking…and that all led to more woodworking-related opportunities. My eagerness and optimism led me to say yes to so many things that at some points I was working from 7am-1am between both jobs (with breaks to eat and work out). This was, obviously, neither ideal nor sustainable.

At this time, in addition to building commissioned furniture pieces, I had a line of home goods I was selling at local stores and craft shows. These items sold really well, particularly during the holiday season. Between markets and restocking stores, and making more goods, my nights and weekends were booked October 1st – December 25th. That is not a great time of year to have no free time.

Between commissions and home goods, the business was cruising along pretty well. I decided to try going part-time with the government. I began this experiment by trimming my schedule to 32 hrs/week and before I resigned I was working the minimum: 16 hours. This gave me more time to work in the shop and try to grow the business, while also having the safety net of remaining employed and going back full-time should I need to do so. This is a really great avenue to try if you need to mitigate risk, as I felt I did.

The thing is, for me, inertia is a very powerful thing. Having two very different pursuits was very challenging mentally; it also strained my ego a bit. At the peak of my office responsibilities, I was leading a large team that worked 24/7 on a major international issue; near the end, I was essentially a part-time consultant. It was difficult at times not to get involved in certain things. By hours 14,15, 16 for the week I was fully in the groove of the office work. But then I’d unplug and get into the shop groove and be very disappointed when Monday rolled around. It was like that famous Robert Frost poem: Two Roads diverged in a yellow wood; I CHOSE BOTH!

2019 ended up being a very tumultuous year for me. In early August, my brother Chris died suddenly; he was only 43. Six weeks later, while riding my bike to my office job, I was rear-ended by the employee shuttle bus. I walked away, literally, but had a concussion and a new appreciation for mortality. About 6 more weeks later, I turned 40. After going through all of that, I just decided that if I wanted to try woodworking for a living, I should. The main determining element of the conversation I had with myself was: try it now while you’re still young(ish). I didn’t want to look back and regret never trying it. It was fine to try and discover it wasn’t right; it wasn’t fine not to do it out of fear.

That’s basically it: your common, run-of-the-mill two-brushes-with-mortality-in-six-weeks/mid-life crisis story. Since going “pro,” the business has changed in ways I would not have expected. And it continues to evolve. More on all of that in the entries that will follow.

Sign up for eletters today and get the latest techniques and how-to from Fine Woodworking, plus special offers.