Going Pro, Part 3: Do You Really Want to Run a Business?

Should you do it? Should you join the ranks of the “professional woodworkers”?

I’ve had this conversation several times, and I really never try to dissuade anyone from trying. I’ll say that I’ve seen several people try it and not last very long, or be very disillusioned. I’ve also seen people jump in faster and deeper than I had the guts to do, and they’ve succeeded in incredible ways (shout out to Austen Morris furniture, my buddy and woodworking neighbor in DC). Certainly everyone’s experience will be different, which is why I think it’s helpful to ask some questions before making the leap.

Do you want to run a business?

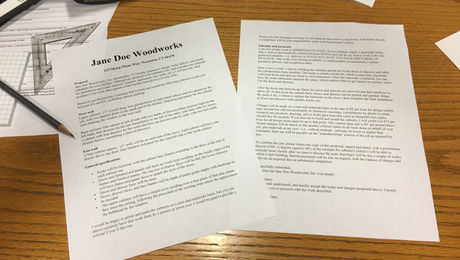

A lot of running a woodworking business is NOT woodworking. In many weeks, I easily spend two to three hours of each day doing some variety of the following: client management, design work, tracking down materials and hardware (either online, or in-person), bookkeeping and taxes, and machine/shop maintenance. A lot of this time is spent “after hours” (in quotes here because when you’re running a business, it’s hard to separate your time). I think some people who are thinking of “going pro” overlook the fact that you’re not simply leaving a job you don’t love so you can just make things all day long. You are, first and foremost, running a business. That will mean finding ways to be profitable, potentially managing people, and spending a lot of time with spreadsheets, QuickBooks, and possibly project management software. You’ll have to market yourself (and this goes far beyond making fun social media videos). You’ll need to build and maintain a website. You’ll probably have to talk to a lawyer, buy insurance, and learn your local tax zoning and business laws.

If you talk to some of the best woodworkers, or even read about their lives, you’ll learn that no matter how skilled you are at the craft, it can be incredibly hard to make money by making things. The skills will not necessarily pay the bills—not alone anyway. (See episode 354 of Shop Talk Live for a great discussion on this very topic.)

How flexible are your skills and your will?

Running a business means giving customers what they want. If you’re financially able and have the skills and design chops, you might be able to hold out and make only the things you want to make. However, this is really difficult to do, and at least initially you may need to take on some things outside of your sweet spot. For me, this meant cabinets, a few built-ins, and some commercial built-outs. I grew to love those paydays but really dreaded the work, particularly working outside of the shop and having other trades depending on my work getting done on time to keep on schedule. It was a lot of pressure.

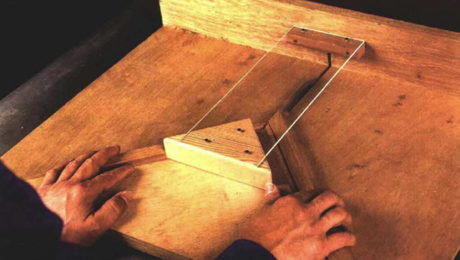

Other woodworkers I know went through similar growing pains. Again, this may be avoidable, but starting out, you may need to take what you can to keep the lights on. Similarly, you will have to make decisions on “value engineering” for your customers. As hobbyists or as fine woodworkers in general, we tend not to want to make any compromises. However, as the totals add up, your customers may need you to help them find some budget solutions: less expensive hardware, pocket screws instead of traditional joinery, plywood instead of solid, etc. Are you willing to put on your business owner hat and make things work for your clients? Or do you simply want to cut crispy dovetails in perfect afternoon light every day?

Do you live for the traditional craft side of woodworking?

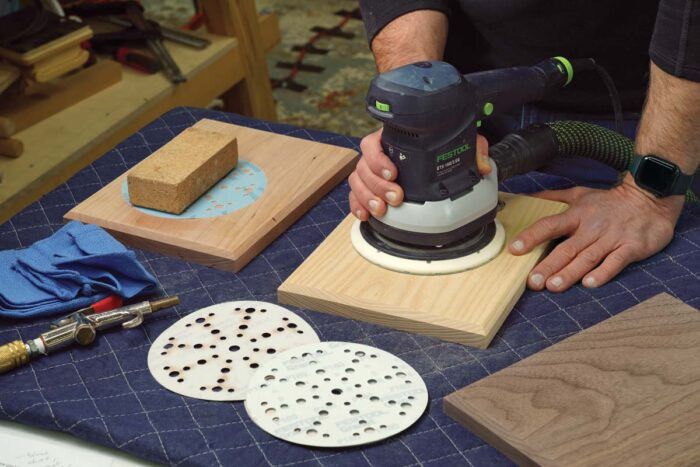

Does your interest in woodworking trend toward sleek chisels, beautiful hand planes, and freshly sharpened dovetail saws? Do you wake up in the morning looking forward to rubbing out that oil finish? Do you have multiple pairs of dividers? Do you have an opinion on tails or pins first? If so, let’s be friends. (Tails first is the only reasonable way, you maniacs.). However, this may not be a reason to consider going pro. People can and do make money using traditional tools and finishes. I count myself among them. However, you need to be equally adept with your power tool skills, consider things like CNCs or Shaper Origin, Pantorouters, Domino joiners, pocket-hole screws, all of the table-saw tricks, and probably also spray-finishing and painting skills. There is certainly a market for hand-tool-only builds, but my experience has been that customers care a lot more about the design, look, feel, and price of a piece than about the particular tools you used in making it.

Have you ever worked in a professional’s shop?

This is a bit of advice from Nancy Hiller that I never followed, and I wish I had. While many hobbyist shops I’ve visited are as well (or in some cases better) equipped as pro shops, the vibe when things are running is very different. I highly recommend spending time working with, or even just visiting, an experienced pro. You will learn a lot about what is involved in the day-to-day running of a woodworking business but also get a ton of good woodworking tricks to keep things moving quickly. You may be surprised by the most-used tools, types of benches, clamping techniques, and general pace of life. It will be illuminating, regardless.

Do you like making money and having spare time?

This is a joke that you’ll hear many pros say. While everyone’s financial needs are different, it’s no secret that it’s not easy to make a lot of money in this field. It is not impossible, and plenty of people do it; I’m not trying to discourage anyone. Even the most talented in the field will tell you about lean times, and most people will experience up and down years. You may need to work very long hours and sacrifice a lot of time with your family to make the business profitable. You may actually do less woodworking than you did as a hobbyist as your business grows and you hire people to help. You may have to find a new hobby to fill the role that woodworking once held for you (if you’re lucky enough to have time for hobbies). Or if you’re like me, you’ll just make dovetailed boxes in your free time.

The things you may not see on social media

Like most things involving humans, there is often more to the story than what you see. Primarily, many people doing this work for a living have other resources supporting them. This is true for me: I had a previous career that served as a “patron” in terms of buying tools and classes. I’m also married, and Jen’s job has a great salary and very good health insurance. Many of the pros I know personally and passingly have similar stories: supportive partners, family support, or a previous career underwriting their current efforts. And even with that support, it can still be difficult.

After all that, I’d still say, “Try it, if you want to.”

Look, I’m not special, and there are a lot of things I don’t know. I provide all of the above to help people make informed and intentional decisions about this based on my experiences and conversations with friends and colleagues in the business. However, this decision could be less consequential than a tattoo: You can always decide to do something else. If you decide to open a furniture business and it doesn’t work out, you can always choose to do something else. Everything has trade-offs, and that includes deciding not to take a risk and wondering the rest of your life about it. The only thing I’d say is not to think that you need to be a full-time pro to be excellent. I’ve had the opportunity to see lots of work by hobbyists that is better than I could do–or is simply something I haven’t even learned yet and may never master (shout out: Albert Klein’s marquetry). There are literally no certifications or licenses or tests to become a pro; anyone can do it. People everywhere are making excellent pieces of furniture, art, sculpture, household items, etc., without all of the pressures of running a business. Do what you want.

Sign up for eletters today and get the latest techniques and how-to from Fine Woodworking, plus special offers.