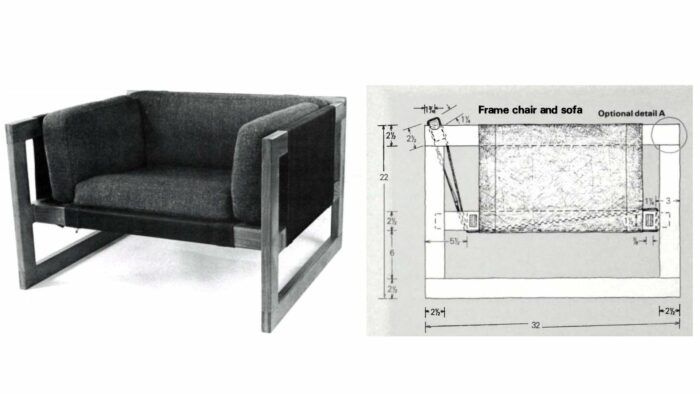

How to make a frame chair and sofa

From FW#22–May/June 1980

This chair and sofa are two variations on one simple theme: a wood frame spanned by tensioned canvas that supports loose cushions. The canvas is kept taut by nylon lacing running through brass grommets. Both pieces are light, easy to make, and economical.

I designed the chair as a practice project for apprentices in their first six weeks of training. It teaches the mortise-and-tenon as well as bridle joints, and it can be made from a drawing with minimum supervision. Since little material is involved, a poorly cut joint could be made over again without either the student or myself feeling badly about the waste.

Later I used the same basic design for a small sofa and then for a larger one. The former succeeded but the latter was a failure. Although amply strong to support three adults, it looked weak because the end frames were too far apart. The only structural difference between the sofa and the chair is in the thickness of stock—1-3/8 in. instead of 1-1/4 in. This is as much for the sake of proportion as for strength.

Sofas are bulky and awkward to move, so I also made a knockdown version by substituting loose wedges for the glued mortise-and-tenon joints. This detail is shown at B in the drawing and can be used for either piece.

This design can be made in any straight-grained hardwood. Before deciding on the wood, consider how it will look against both the canvas and the fabric chosen for the cushion covers. I like a black canvas because it doesn’t show dirt, goes with any wood (except walnut), and looks good with brass grommets and white lacing.

Construction

Starting with 6/4 stock, cut out the pieces for the end frames and rails. If you are making the knockdown version, be sure to add 3 in. to two of the long rails to make room for the mortises and wedges. Mill all these pieces down to 1-3/8 in. if making the sofa, 1-1/4 in. for the chair.

The next step is to join up the end frames by bridle joints at each corner. Bridle joints are best cut on the table saw; a carbide blade helps ensure accuracy and smoothness. If I were making this chair by hand, I would use a different joint, a mitered dovetail, because I don’t like to do things by hand that are better done by machine and vice-versa. I’ll describe how to make the bridle joint first, then the mitered dovetail.

After cutting the pieces to length, set a marking gauge to the width of the stock plus 1/16 in. Mark out one of the pairs to be joined on all four faces of each piece. If you are using a table saw, there is no need to mark more than one pair because saw and fence settings will take care of the rest. Usual practice is to make the tenon two-fifths of the thickness of the stock—about 1/2 in. for 5/4 stock.

Saw the tenons. I cut the cheeks first, then the shoulders. If you don’t have a good enough blade for finish cuts, mark all the shoulders with a knife, saw 1/16 in. in on the waste side and then chisel to the line. The shoulder must be left square, not undercut, because it shows. Next saw the mortises. Since you’ll be holding the pieces vertically, you need a way to support them so they don’t dangerously tip or wobble. A tenoning jig is a good idea.

The mortises should fit the tenons snugly without any forcing.

You can saw the entire mortise, or just the walls. If you go the latter route, remove the waste in between by drilling a single hole (halfway from each side) or with a coping saw. Then with a chisel, clean up the end grain to the gauge mark on the inside of the mortise.

The mitered dovetail, the handmade alternative, is a one-pin affair that does the job of a bridle joint, only more elegantly. Begin by marking all four surfaces of each pair to be joined (dotted lines in the drawing at A). Mark out the miter lines on each side of both pieces with a knife, but do not saw them yet. Next, mark out the space for the tail on the horizontal piece (a) as shown. This can be sawn either on a table saw, with the blade angled, or by hand using a tenon saw. Cut out the waste with a coping saw and chisel to the line y-y working from both sides. Lay piece a firmly on the end of b and mark the pin with a scribe or thin-bladed knife. Mark out the other limits of the pin and saw the cheeks. Remember to stop the sawcut when close to the miter line.

The last step is to saw the miters on both pieces and trial-fit the joint. You should saw the miters a little to the waste side of the line, push the joint together and then run a fine saw into the joint, on both sides, until the miter closes.

With the joints in the side members cut, the middle rail is next mortised into the two verticals and then all five frame pieces can be assembled and glued up. When gluing a bridle joint, be sure to put clamping pressure (protecting the work with pads) on the sides of the joint until the glue has set. When gluing a mitered dovetail, put glue on the miters as well as on the pin and tail. Clamp lightly across the cheeks of the tail. Check with a square. After the glue has set (but before it is bone hard), flush off the surfaces with a sharp plane.

Next, cut the through-mortises for the two long rails. Mark accurately on both sides with a knife, drill out the waste, then chisel to the knife mark. The semicircular cutouts are best done by clamping the top edges of the two frames together and drilling a single 1-1/4-in. hole. Remember to use a backing piece to prevent splintering.

The edges of the frames and rails must be rounded over. If they are left sharp, the canvas will eventually wear through on the corners. I use a router with a carbide roundover bit fitted with a bearing. It can also be done by hand, with a wood file and sandpaper. All the edges are treated in the same way except where two horizontal rails meet. Here they are left square.

Next, the four pieces of the underframe are cut and joined. The short pieces are stub-tenoned into the long rails because a through-mortise would weaken the structure. This assembly is then attached to the end frames using either a glued-and-wedged mortise-and-tenon joint or, for the knockdown alternative, a through-mortise and loose wedge. In both cases the wedge is vertical, at right angles to the grain.

When making a tapered mortise, it is best to make the wedges first. Lay a wedge on the outside of the tenon and mark the slope with a pencil. Then, with a mortise gauge and a knife, mark the two mortise openings top and bottom. Most of the waste can be drilled out (working from both ends) and the remainder cleaned out with a chisel. I always leave the wedges 1 in. overlong so when they are tapped home they can be marked, then removed for trimming. The top of the wedge should project slightly more than the bottom. In time they invariably get driven lower.

The top rail, at the back of the chair, is not fastened but is held in place by the tension of the canvas. It is rounded on the upper side and fits loosely into the half-rounds in each frame. Its two ends are best sawn out square and then shaped with a rasp or wood file.

The canvas is wrapped around the completed frame and laced across the back and under the seat. You will need 45 ft. of 1/4-in. lacing, double for the sofa, which must be nylon or an equivalent. Don’t use clothesline or sash cord. I use an 18-oz. treated chair duck, which is a rather heavy material for a domestic sewing machine, and you may want to have the canvas made by a tent and awning manufacturer, a sailmaker, or an upholsterer. The 2-in. seams are sewn with the edge turned under 1/2 in. They must be made exactly as in the drawings so only the smooth side of the seam shows. The brass eyelets, or grommets, are easy to put in yourself. You need about three dozen 1/2-in. grommets (five dozen for the sofa) and a 1/2-in. punch-and-die set.

Cushions

To make the cushions you need a piece of medium-density polyurethane foam 4 in. thick, 1-in. Dacron wrapping, medium-weight unbleached muslin, a 26-in. zipper for each cushion, and fabric for the outside covers.

First make a full-size pattern of each different shape of cushion in heavy, brown wrapping paper. Transfer the patterns to the foam using a soft pencil or blue chalk. If you don’t have a bandsaw, the easiest way to cut polyurethane is with a fine panel saw or hacksaw. An electric carving knife will work, too. Support the foam on the edge of a piece of plywood, saw with light strokes along the lines, and keep the plane of the saw vertical.

The Dacron batting gives the cushions some extra bulk and makes them less hard—both on the seat and on the eye. They are padded a little more on one side than on the other as follows: Using the same patterns, cut out with scissors one piece of batting for each cushion. Lay this on the side of the foam, which, when in place, will be toward a person sitting in the chair (away from the canvas). Next wrap each cushion, including the ends, once around with the batting. You may want to keep this in place with a spray glue (foam or fabric adhesive) while making the muslin undercovers. To cover the ends of the foam, either cut the batting over wide and fold it over the ends, like wrapping a parcel, or cut separate pieces of batting and spray-glue them in place.

Undercovers

Muslin undercovers are essential. Without them it is practically impossible to remove and replace outer, or slip, covers, for cleaning. Inner and outer covers are made in the same way: two panels joined by a strip (called boxing) that runs around the edge of the cushion.

Lay the original patterns on a piece of newspaper and then, with a felt pen, draw a line around them. Draw another line 1/2 in. outside the patterns and a third one 1/2 in. outside that. Cut around the outside line. Using these new patterns, cut out two pieces of muslin for each cushion. Next, cut the boxings, strips 4 in. wide and a little longer than the perimeter of the cushion. They don’t have to be one piece.

If you are an old hand with a sewing machine, machine stitch the covers directly, sewing 1/2 in. from the edge of the material (the middle line of your pattern). This is best done by putting a piece of tape as a guide on your sewing machine 1/2 in. from the needle. Sew the boxing to one panel all the way around and then, starting from one corner, sew the other panel. If you are a novice, pin or hand-stitch (baste) the covers before machining. Leaving one long edge unsewn, turn the covers inside out and insert the wrapped foam. The loose edge is turned under and blind-hemstitched by hand.

Fabric

As in choosing a wood, certain criteria apply when picking fabric for the outer covers. Leaving aside matters of color and pattern, you must choose a fabric that is strong enough. It must not stretch in use—which means a tight weave— shrink when washed, or wear too quickly. Think of the climate, too. Wool is fine in Vermont, but it would be a poor choice for the heat and humidity of a Washington summer, where linen or heavy cotton would be preferable. Remember that light colors need cleaning more often, blues fade in bright sunlight, and some synthetics not only can melt but are flammable. The chair will require 5 yd. of 30-in. to 36-in. material, the sofa 8 yd. If you use 48-in. or 54-in. material, the chair will require 4 yd. of material, the sofa 6 yd. The undercovers will require roughly the same amount of muslin. Make sure the material is preshrunk. If it is not, you must wash it once to shrink it. Ironing makes the sewing easier.

Outer covers

Taking the same newspaper patterns that were used for the muslin covers, cut (to the middle line) all the way around. Then pin the patterns to the fabric and cut out the panels as before, together with enough 4-in. strips for the boxing. The innermost line on the pattern is now the one to sew on.

The alert reader will notice that the muslin-covered cushions are ½ in. bigger than the outer covers. Like putting a sausage in its skin, this helps keep the outer covers tight and free from wrinkles. Wrinkles in the muslin will not show through—the muslin is too thin.

The inner and outer covers are made exactly the same way, the only complication being the zipper. This must be put where it won’t show, and the best placement is indicated on the drawing. To install the zipper, take a piece of boxing 1 in. longer than the zipper and fold it in half lengthwise, making a crease. If it won’t stay creased, iron it. Lay the zipper down on the crease so that the zipper teeth are just level with the folded edge of the boxing. Pin or tack it in place and then stitch it using the zipper foot of your sewing machine. Now take another piece of 4-in. boxing, crease it lengthwise, and stitch it to the other side of the zipper. You should now have a 4-in. strip of boxing, double thickness, with a zipper running neatly up the middle.

When sewing this piece of boxing to the side panels, remember to face the zipper in. Then, when the cover is turned inside out, it will be on the right side. A professional upholsterer covers the two ends of the zipper by overlapping the adjacent boxing. Or, you can simply join it with a neat seam.

It is a good policy to sew the seams twice, once along a line ½ in. from the edge and again as near to the edge as you can manage. This prevents the material from unraveling at the seam if it is roughly laundered.

This chair and sofa have never been made in quantity but the design could easily be adapted for production by machine. This is because there is no hand-shaping, boards do not have to be selected for color and grain, and most of the joints can be cut by machine. The design could be further simplified by using only one thickness of stock (1-3/8 in.), which would cut the number of separate parts in half. Bridle joints lend themselves to machine production, but I would replace the mortise-and-tenon joints with stub mortises using Allen-head machine screws and T-nuts. The whole piece could then be knocked down and easily reassembled.

Sign up for eletters today and get the latest techniques and how-to from Fine Woodworking, plus special offers.