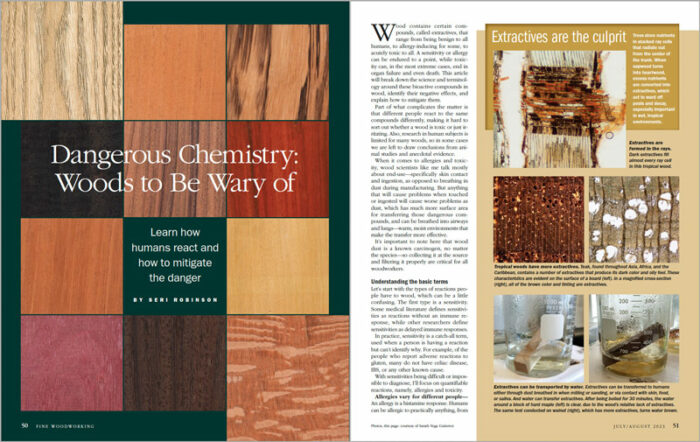

Wood allergies and toxicity – FineWoodworking

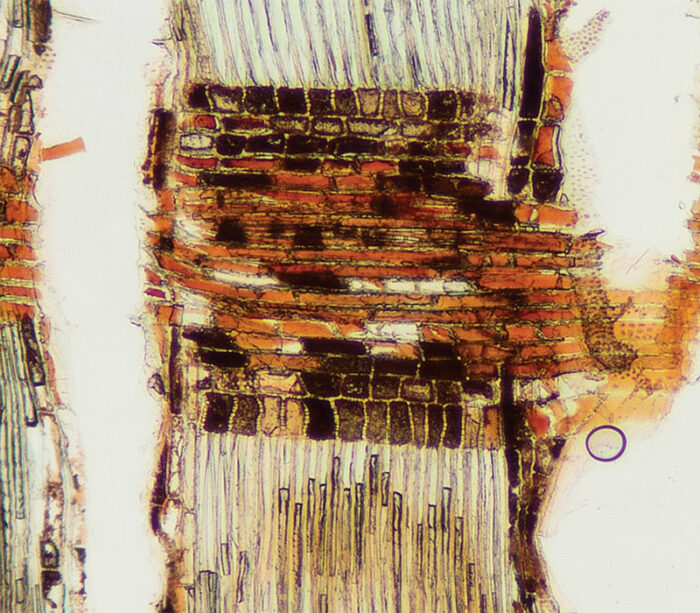

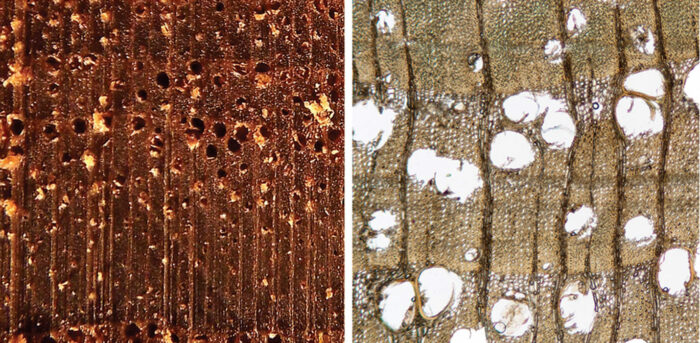

Synopsis: Some woods can cause an irritating skin reaction, as many woodworkers know. That’s because of compounds called extractives, which act to ward off pests and decay. Your reaction to these compounds can range from mild to extreme, depending on your personal makeup, so it makes sense to study up on woods you plan to use. Here is a look at common woods and where they fall on the scale from benign to allergy-inducing, to toxic.

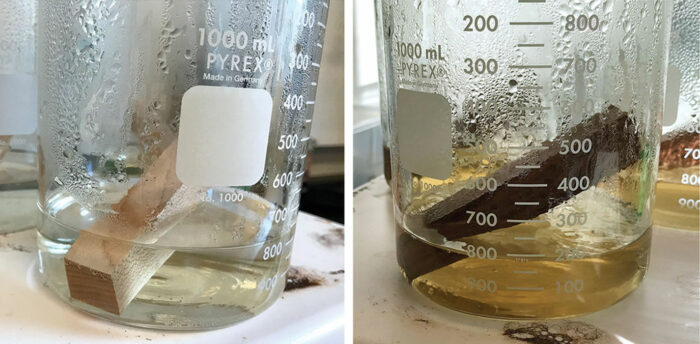

Wood contains certain compounds, called extractives, that range from being benign to all humans, to allergy-inducing for some, to acutely toxic to all. A sensitivity or allergy can be endured to a point, while toxicity can, in the most extreme cases, end in organ failure and even death. This article will break down the science and terminology around these bioactive compounds in wood, identify their negative effects, and explain how to mitigate them.

Part of what complicates the matter is that different people react to the same compounds differently, making it hard to sort out whether a wood is toxic or just irritating. Also, research in human subjects is limited for many woods, so in some case we are left to draw conclusions from animal studies and anecdotal evidence.

When it comes to allergies and toxicity, wood scientists like me talk mostly about end-use—specifically skin contact and ingestion, as opposed to breathing in dust during manufacturing. But anything that will cause problems when touched or ingested will cause worse problems as dust, which has much more surface area for transferring those dangerous compounds, and can be breathed into airways and lungs—warm, moist environments that make the transfer more effective.

It’s important to note here that wood dust is a known carcinogen, no matter the species—so collecting it at the source and filtering it properly are critical for all woodworkers.

Understanding the basic terms

Let’s start with the types of reactions people have to wood, which can be a little confusing. The first type is a sensitivity. Some medical literature defines sensitivities as reactions without an immune response, while other researchers define sensitivities as delayed immune responses.

In practice, sensitivity is a catch-all term, used when a person is having a reaction but can’t identify why. For example, of the people who report adverse reactions to gluten, many do not have celiac disease, IBS, or any other known cause.

With sensitivities being difficult or impossible to diagnose, I’ll focus on quantifiable reactions, namely, allergies and toxicity.

Allergies vary for different people

An allergy is a histamine response. Humans can be allergic to practically anything, from peanuts and pollen to dust and dander. And allergic responses tend to build with multiple contacts. For example, the first time you work with eastern red cedar you might not react, but the second time you might break out in hives. This process of becoming more allergic to a compound over time is known as becoming “sensitized” (not to be confused with a sensitivity). There are many compounds in wood that can build a heightened allergic response over time— particularly in aromatic woods, such as the cedars. Whether you react on your first or fifth exposure is a product of your unique biology.

Once you are allergic to something, your body’s response can be similar to a toxic response, so in many applications, you should treat allergens similarly to toxic compounds.

Toxicity is universal

The term toxic indicates that the response to a compound is similar for all humans. If every woodworker sneezed in the presence of cedar, it would not only be considered an allergen but also toxic. Toxic reactions range from drowsiness, contact dermatitis, hives, and respiratory issues to genotoxicity—the potential to damage DNA and chromosomes, which can be passed down genetically.

There are some toxic compounds that can be released from wood, such as safrole from sassafras. While raw wood isn’t currently regulated by the FDA, some of these released compounds are. So it’s easier to find information on them.

—Seri Robinson, PhD, is a professor of wood anatomy, an avid woodturner, and the author of numerous books on turning, spalting, and wood technology.

Photos, except where noted: staff.

For more photos and information, click the “View PDF” button below:

Sign up for eletters today and get the latest techniques and how-to from Fine Woodworking, plus special offers.

Download FREE PDF

when you enter your email address below.