Pat Moriarty’s new shop in an old mill

Synopsis: After retiring as a mechanical engineer, Pat Moriarty launched a chair company and began planning a freestanding woodshop on his property. However, when he learned that an old industrial building in a neighboring town had been converted into a space for artists, makers, small businesses, and startups, he abandoned his original plan and signed a lease for a space that would accommodate his vintage woodworking machines. Not only did Moriarty get immediate access to a perfect space for his business, but he became part of a community of creators, some of whom he has collaborated with.

When I retired after a career as a mechanical engineer nine years ago, I knew that I wanted to spend the rest of my life doing something that was both exciting and challenging. Having already enjoyed years of woodworking as a hobby, I decided it was a natural choice for the next chapter of my life. Within a week of retiring, I started Conway Chair Company.

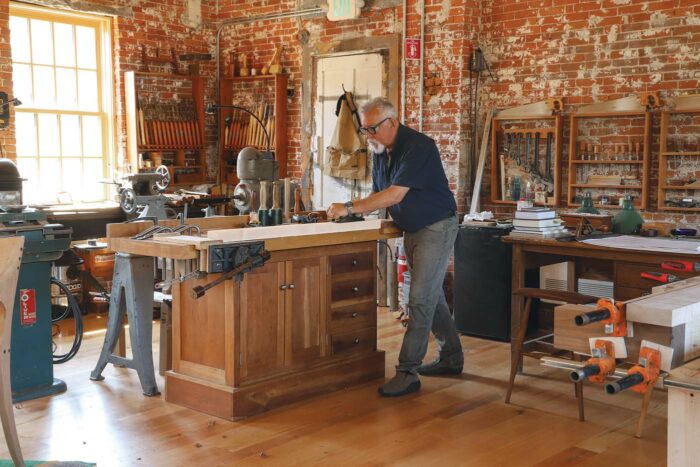

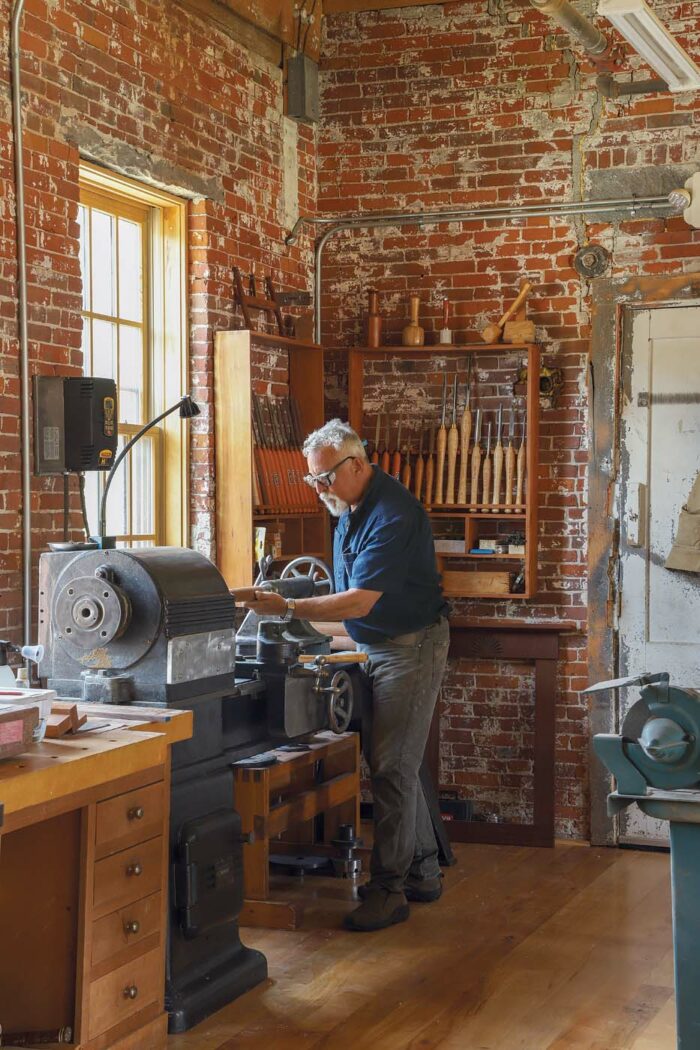

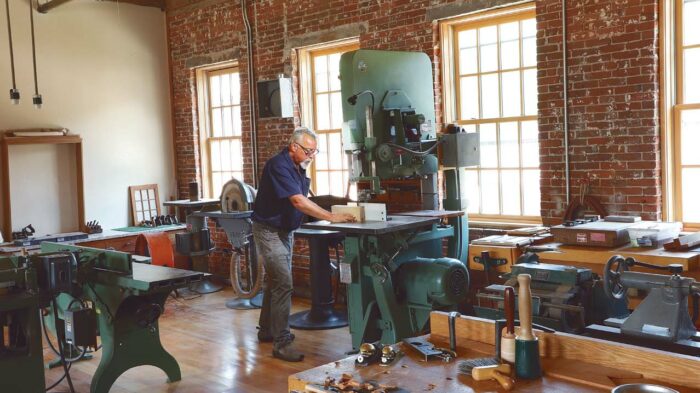

This struck me as a great opportunity, and the next day I was negotiating a deal with the owner of The Mill at Shelburne Falls for a 30-ft. by 25-ft. space featuring hard maple floors, tall double-hung windows that line the east and west walls and fill the space with sunlight throughout the day, and three-phase 230-volt power for all of my woodworking machines.

I immediately loved the space, and over time I’ve discovered that having a shop situated in a building repurposed specifically for creative endeavors is an enormous benefit. Being immersed in a community of artists and makers, each with their own skills and working on their own projects, leads to a contagion of creation. For me, this arrangement has spawned inspiring collaborations with fellow tenants (there are about 40 of us now) and has increased public visibility of my work through both casual contacts and building-wide open-studio events held throughout the year.

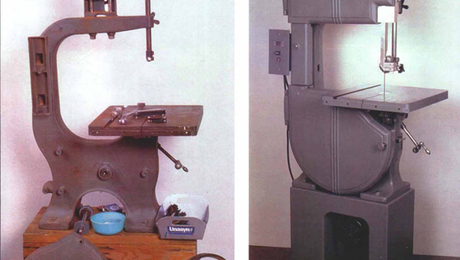

I had been finding and restoring old woodworking machines for many years, and now all of them have a home. Each vintage machine has a story. My 36-in. 116 Oliver bandsaw originally resided at the Charlestown Naval Shipyard and was used to help restore the U.S.S. Constitution. Then there’s my Northfield 12 HD jointer, with its 3-hp, direct-drive motor and straight three-knife cutterhead. It departed the Minnesota Northfield factory on July 2, 1941, to an unknown destination. Sixty years later it was in use at McIntosh & Tuttle Cabinetry Company in Lewiston, Maine, and in 2005 it was acquired by the New Hampshire–based Littleton Millwork Company. I purchased it from Littleton for practically scrap value. When I was restoring this tool top to bottom, Northfield Machinery Builders—still in business!—provided me with parts, labels, and consultation. This exact machine is still made by Northfield today. My shop’s oldest machine is an Oliver No. 3 miter trimmer, which was made sometime before 1905. I use a 1950s Hammond Glider Trim-O-Saw to cut shoulders on tenons and make crosscuts on four-square stock. The Hammond Glider was originally used in the printing business to cut lead letter stock, and its principal feature is a cast-iron table that slides on rails. This feature makes it a superb tool to use when exact dimensions are critical. Similarly useful is my 1945 Walker-Turner radial drill press, which was originally owned by Pratt & Whitney. This machine’s three-axis drilling ability suits it perfectly for cutting compound-angle mortises in chair seats.

Purchasing vintage woodworking equipment requires a good deal of perseverance and due diligence. I never buy equipment that has any casting defects (like cracks or previously repaired cracks) or is missing critical components. I prefer to buy directly from fellow woodworkers, I never buy sight unseen, and I always bring tools to assist in the evaluation: dial indicators to check for arbor run-out, straight edges to check for table flatness, an ammeter to check the motor health. And the restoration process can be quite time-consuming. But the pleasure of using great old machines in this great old building makes it well worth the effort.

Sharing a building

|

-Pat Moriarty makes chairs in Shelburne Falls, Mass.

| From Fine Woodworking #314

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below. |

|

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Makita LS1219L Miter Saw

This is the saw I want in my shop. For one, it’s easy to use. All of the controls are easy to reach and manipulate, and the glide mechanism is both robust and smooth. The handle works well for righties and lefties. Then there are added bonuses that no other saw has. For instance, its hold-down is superb, as it can move to different locations, hinges for a greater range of coverage, and actually holds down the work. In addition, the saw has two points of dust collection, letting it firmly beat the rest of the field. The one downside was the saw’s laser, which was so faint we had to turn off the shop lights to see it. Still, all these pluses in a package that fits tight to the wall? That’s a winner for me.

Ridgid EB4424 Oscillating Spindle/Belt Sander

With five spindles sized from 1/2 in. to 2 in. and a 4 X 24-in. belt, this sander has become a staple in many a shop Fine Woodworking visits.

JessEm Mite-R Excel II Miter Gauge

The gauge has a quick and easy method for fitting the guide bar precisely to your tablesaw’s miter slot. This means the gauge can be recalibrated if necessary for continued accuracy. The face of the protractor head can be adjusted square to the table and also square to the guide bar. This ensures accurate cuts, and it, too, can be readjusted if the need arises. The protractor head has stainless-steel knobs and fittings and high-contrast, easy-to-read white numbers and increments.

Sign up for eletters today and get the latest techniques and how-to from Fine Woodworking, plus special offers.

Download FREE PDF

when you enter your email address below.