Throwback: Edward Barnsley – FineWoodworking

—This article is from FWW #16–May/June 1979.

In England many people consider Edward Barnsley to be the grand old man of furniture designers. What category of designer? Well, far outside the furniture trade.

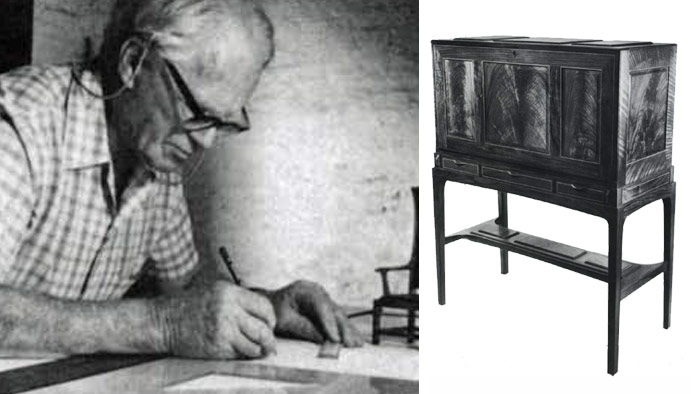

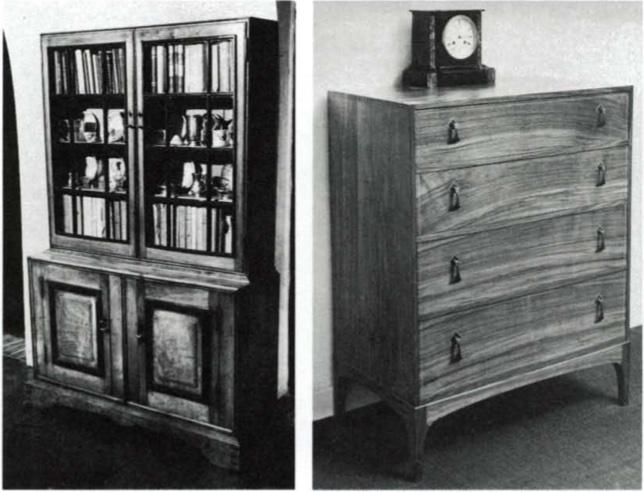

Let’s say he works in what has come to be known as the “English handcraftsman’s tradition,” which has roots threading back to both 18th-century folk or farm furniture and (I would reckon more importantly) to the neo-Classical strictness of spare, unadorned pieces by Sheraton or Hepplewhite. “Designer and craftsman” is how Barnsley defines himself. I illustrate the point with two pieces of which I think he is modestly proud, one from 1924 and one from 1965. He designed and made both.

To our restless age, Barnsley does his best not to belong. He has made but one major geographical move, across southern England from the Cotswolds where he was brought up, to Hampshire, where he settled half a century ago. His work and life appear to be inextricably fused—the pedigree of the mix goes back to the Victorian craftsmen-philosophers John Ruskin and William Morris.

Like many lesser and forgotten men, William Morris cold-shouldered the Victorian industrial scene. He took off for the unspoiled Cotswold countryside and became what is today called a guru. But unlike Morris, Barnsley had no pressing need to rebel. In 1900 he was born into a tradition that suited his temperament and his talents. His destiny (a hard one) has been to remain faithful to that position, as far as possible.

At the center of that tradition is Ernest Gimson, “a craftsman endowed with the ability of a designer,” who brought an individual genius to furniture making that had been lacking since the death of Sheraton. Gimson, who had met Morris in 1884 and had been fired by his luminous vision, passion, and practical drive, was the leading spirit in the Gloucestershire villages where Barnsley’s father, Sidney, and his uncle, Ernest, both qualified architects, had put down roots.

Gimson took on a pupil named Geoffrey Lupton, and over time, Lupton, initially a trained engineer and an able craftsman, began running a small furniture workshop at Froxfield, a scattering of houses and farms above the market town of Petersfield (about 60 miles southwest of London). After working alongside his father and spending a year at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London, Barnsley, in 1919, was apprenticed to Lupton at Froxfield.

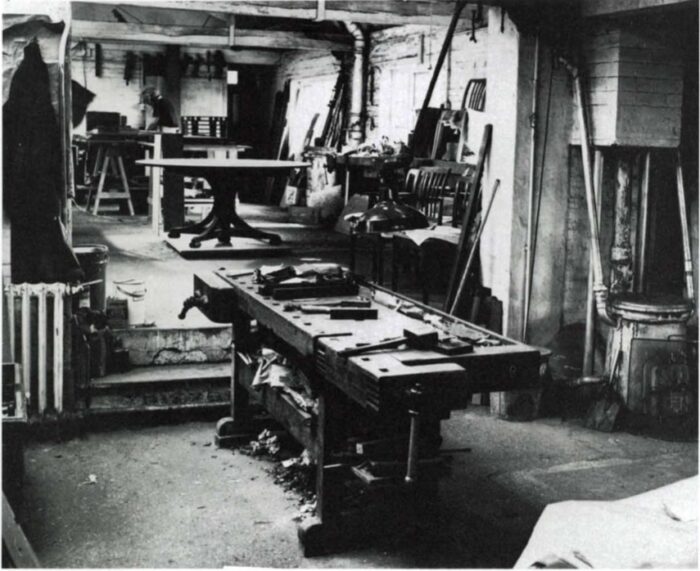

In 1923 he rented the shop from Lupton and three years later, backed by his father, bought the place. Since that date, Barnsley has enlarged it. Over the years Barnsley in his turn has taken on many pupil-apprentices and worked closely with several craftsmen. The number has fluctuated—as I write, three craftsmen and one apprentice remain.

The Barnsleys’ home and the shop are as good as joined one to the other, although to enter the shop you walk through the open air, over a gravel path on the garden side. A sizeable vegetable garden, industriously cared for, some beautifully kept herbaceous borders, and an uneven lawn slope down to a retaining wall.

At a man’s height below lies a narrow terrace where fruit trees in summer shade the rough grass. Beyond these limits, the land plunges and funnels toward Petersfield. Looking back uphill, the house and workshop sit comfortably just above the rim of the escarpment.

Lupton designed the Barnsley home, which from the outside looks much larger than when you go indoors. A compact kitchen huddles next to the living room, a plain, all-purpose space—the mood set partly by the satisfying volume and partly by the subtle tones of the woods used for furniture, doors, and floor.

Several focal points compete mildly for one’s attention: a portly oak sideboard dresser made by Barnsley’s father. Below a bowed lintel, a finely proportioned main window. The generous open hearth, rebuilt by Barnsley and probably as efficient as an open fire can be. A walnut bookcase cabinet rests unobtrusively between massive doors.

On either side of the hearth you might notice a couple of walnut burls, those fascinating and freaky things sliced from outgrowths at the base of some walnut trees, in a section well above an inch thick. The convoluted swirlings evoke for me those patterns of human lungs seen in medical textbooks.

Some years ago Barnsley held them up for my wife and myself to look at: He studied our faces as if to discover whether we shared the awe he seemed to feel. They must represent a deep involvement with the organic and reflect his philosophy of wholeness. They can also be thought of as the raw nuggets from which walnut figuring is mined.

From the desk by the wide living room window, as well as from the windows by Barnsley’s drawing table, the eye travels over the treetops towards a distant patchwork of husbanded land. The views encourage the mind to loosen up and stretch itself. “Could anything be more beautiful?” Barnsley asks rhetorically.

On a clear day, I unwind as I gaze beyond Barnsley’s desk at those views. My gaze on a mournful day turns indoors and down at the floor. Great broad oak boards, mellow and burnished. Timeless impregnability—unless the air and sky are ripped open by a low-flying jet.

Despite his 78 years, Barnsley is still an active man who knows how to recharge his batteries with effective catnaps. At the proper season, he may be up before six. Compost to be moved. Garden timber to be felled and bow-sawn, split, then stacked in a measured manner for hearty winter fires.

You pass on one route to the shop a high and meticulously ordered wall of logs. Barnsley leads the way. Saunters into the main L-shaped shop. Moves with the firm, composed, relaxed motions of an open-air man. A fluent, witty, and entertaining host he can be.

Also a thoughtful-complicated talker ready to ruminate on his attachment to nature, or rake over the embers of the independent designer-craftsman’s predicament in a philistine world. But here in the shop, there are long speechless intervals, ample pauses for one to relish the textures and tones of walnut, oak, cherry, cedar, elm, yew, rosewood, or mahogany.

Beech and ash are not for him. Time to appraise a chair, a secretaire, a cabinet or bureau or side table, whatever piece or set of pieces is nearing completion or, if complete, awaiting delivery.

Two craftsmen are using their practiced hands; another concentrates on a machine. A machine? That’s the word the Froxfield craftsmen use. But Barnsley insists we shall talk of tools or powered tools.

“Essential to call these things tools, not machines. The word tools conveys something different from the word machine. Great skill is still needed to use ‘power’ tools but in a different form to handwork.” So much for semantic niceties. Young apprentices coming to Froxfield learn to do things the hard way. This allows them to understand the problems they face. Says one of the craftsmen,” Later on when they’ll be using machines, having learned the basic way with tools, they’ll use the machines more sensibly.”

These machines were brought in around 1950. Somewhat earlier came the first arrivals, first of all, a treadle circular saw. All hands aboard if anything of any thickness had to be cut. Later, a mortiser was bought. “You heaved on the handle to cut out the mortise.

You turned a handle to move the bed along to cut longer mortises. Not a very successful device.” (Now they’re on their second hollow chisel mortiser, “a beautiful thing. Cuts truer than a man could ever cut. A circular saw driven by a gasoline motor next appeared. Later, electricity found its way in A jointer, and thickness planer “took the hard graft out of planing”; a bandsaw, panel sander, spindle-molder, and the modern mortiser found space.

“It is possible,” Barnsley now says, “in a day of eight hours to carry out with extreme exactitude as much work as could be carried out in two or three weeks by hand.” The voice, I suspect (perhaps wrongly) is that of a reluctant convert.

There must have been much heart-searching before the powered tools, not to mention blockboard and synthetic glues, forced their way into the Froxfield workshop. Plywood still sticks in Barnsley’s throat, although his craftsmen don’t mind it. The techniques of bent lamination, where you resaw your laminates, are very much in favor.

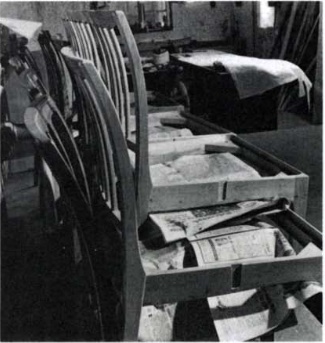

We are standing close to a set of chairs and the way they are stacked makes a fascinating pattern. Barnsley rests a forefinger on the cherry-top back rail of one of the chairs. “Just look at this—” Barnsley marvels, so it seems, that any man should possess the unfaltering ability of producing identical curves. His tone also conveys unstinted praise for the patience, dexterity, and accuracy of his craftsmen.

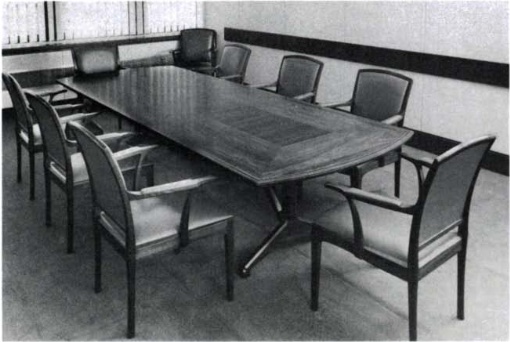

Barnsley’s chairbacks (these were made in 1964 of rosewood for the dining room of the Courtaulds Company in London) have an agreeable orthopedic quality—a faintly convex profile that supports well-worn vertebrae. Their graceful arms are reminiscent of some 17th-century Windsors.

The table top is veneer on plywood, with sycamore inlay around the perimeter. A form for the back rail is made, set out, and molded on a jig. A fine bandsaw speeds replication. Before you sandpaper back to the line by hand, a sanding block revolving at about 1,000 rpm is used. Do I only imagine that an undertone of regret or nostalgia weighs on Barnsley? Shouldn’t each chair present a barely visible flaw to differentiate it from the next?

The stack of chairs that seized my eye awaits the fitting of their arms. Joints on the seat rails have already been prepared; this overcomes some of the awkwardness of coping with a job that doesn’t sit on the bench very well.

A private dining room may require four chairs and two armchairs. For a boardroom of Courtaulds, a leading British company, Barnsley’s shop produced two dozen identical chairs. In the same year, 1964, Froxfield made dining room furniture for the same firm. The shop occasionally produces ceremonial chairs too—one, with a prayer desk, was commissioned by Canterbury Cathedral.

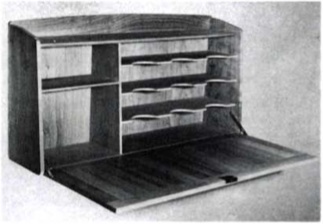

We have now left the main shops and linger in a backwater of the passage leading to Barnsley’s design room. I find myself looking at a simple, practical piece which might be called a hanging bureau.

Five of these utilitarian paper tidies, in cherry, are destined for the sons and daughters of one of the many Barnsley clients. The shelf fronts are scooped to give easy access to papers and documents. The design conforms to a Barnsley maxim: fitness for purpose and pleasure in use.

Not only the specific needs of customers but the site or probable site of a piece is taken into account. A long rosewood sideboard [pictured above] was initially planned for use in a narrow corridor, though it is now at home in a spacious living room. Barnsley thinks of this particular sideboard as “one of our best pieces.” Nearly all his furniture is made to measure.

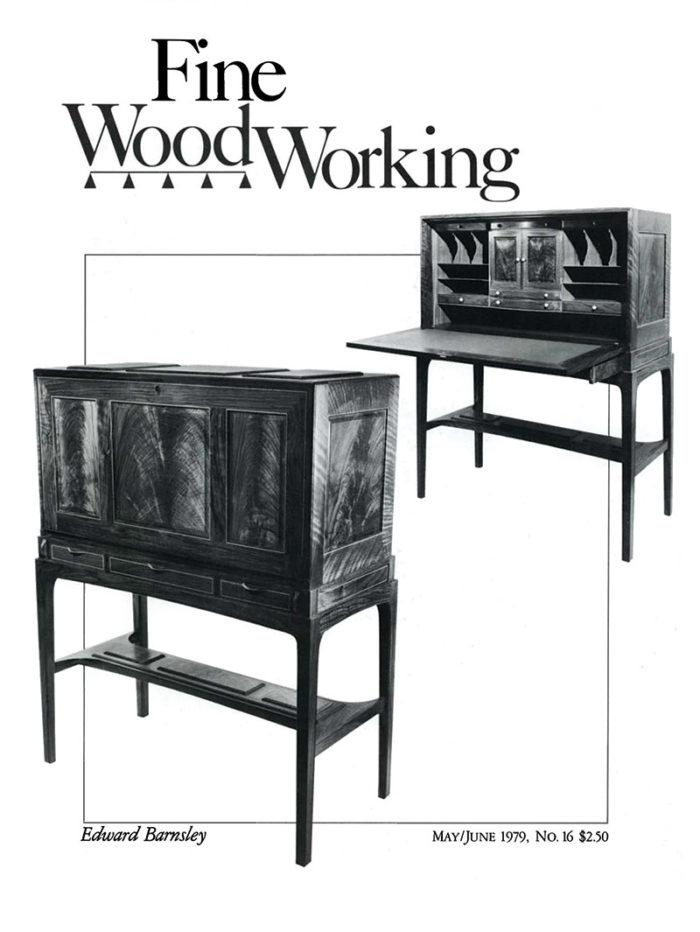

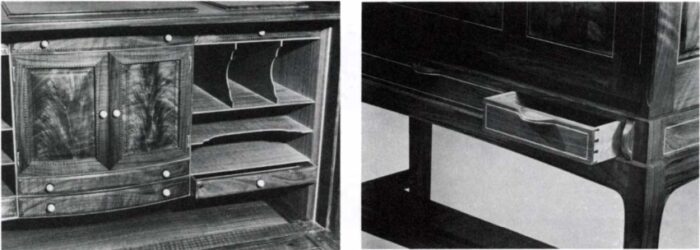

On turning around, there staring at me is an exceptional artifact—a no-money-spared writing cabinet that could make a reputation all by itself. It has attracted a well-favored name, the Jubilee Writing Cabinet or the Jubilee Piece.

Jubilee refers to the 25th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation. The cabinet went up to London and was shown there in 1977 at a Masterpiece Exhibition mounted by the Crafts Advisory Committee. Some admirers of Barnsley’s work have used the word “ornate” to describe this piece, which certainly may go beyond his usual sober austerity. A matter of taste; for me, “ornate” is a bit too strong.

After I have studied the cabinet from a multiplicity of angles, Barnsley, who is given to understatement, says,” I think we’ve got it about right.” Half assessment, half interrogation. There is an unspoken question concerning its undoubted excellencies and possible infelicities. The underneath stretcher has been a great headache.

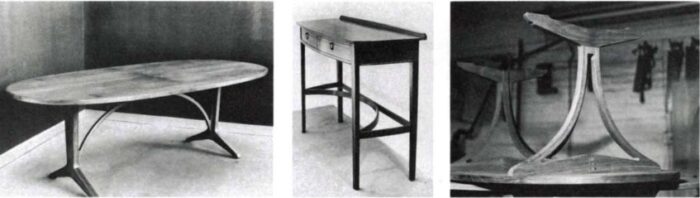

Bottom structures can be a fascinating challenge. How to prevent knees from colliding with essential parts? How to make it easier to sweep underneath or allow chairs to be placed below a top? In the case of tables, Barnsley has produced some eloquently functional ideas, for example, the pedestal supports with quarter-legs soaring upwards from low-pitched straight feet.

The Jubilee writing cabinet made its debut with a framed-up structure comprising three panels, raised and fielded, with the end stretchers mortised and tenoned into the legs. Corner brackets have been tongued and glued into the corners of the framing—in this way the long, broad rail swells at both ends.

Several experiments led to this solution. At one stage, borrowing from one of Barnsley’s well-tested designs went forward into the shop. A hooped stretcher was to sweep upward, vaulting beneath the center of the underside of the carcase.

The end stretchers were made and the rail was laminated. But Barnsley was not happy with the effect. The next move included making a back stretcher and clamping it to the rear legs of the stand. The hooped stretcher rail was tipped into the horizontal plane and its ends were set against the front legs of the base. The geometry now was similar to that of a small rosewood side table (below) made in 1962.

It measures 84 in. long and 42 in. wide. The bow-front side table (1962), center, is rosewood inlaid with sycamore and measures 42 in. long and 33 in. high. Right, a typical laminated table understructure. The curved legs are attached to the feet and top bearing rails with splines instead of mortise-and-tenon joints, with the grain of the spline crossing the line of the joint.

Again Barnsley was dissatisfied. Perhaps the sweeping curve clashed with the strict classical lines of the cabinet as a whole. For whatever reasons, the seduction of a curving stretcher was abandoned.

The change between visualization on the drawing board and the setting out of the shaped pans is all in the day’s work. What happened next was less predictable, given the patient thought and infinite care taken over procurement and storage of timber at Froxfield: the woodworker’s nightmare—twisting.

Barnsley shakes his head and mutters darkly, “Central heating has a way of shrinking panels disastrously. Disastrously.” Somehow, for the cabinet’s fall front or flap, as well as for the rest of the carcass, shrinkage was to be outmaneuvered, despite its being made of solid wood, not veneer.

Seasoning, perhaps kilning, and exacting acclimatization surely would do the trick if the right timber were selected. “There’s a place for every piece of wood and a piece of wood for every job—if you can find it,” Barnsley says.

Barnsley and his foreman-manager, Bert Upton (at Froxfield since 1924), are great squirrels when it comes to timber hoarding. This goes back to the days when everything was cut from the solid and it was necessary always to have ready a supply of naturally curved pieces appropriate for a repertoire of predictable shapes.

Nowadays, off-cuts are likely to serve for outside laminations or solid fielded panels and hoarded for use on special occasions. Making the Jubilee writing cabinet was just such an occasion.

For the cabinet’s fielded panels, a type of figured walnut spoken of as “flames” or “feathers” was used. Flames are taken from the junction where the tree forks. To come up with matching flames was a teasing demand, but the large front and rear central panels and the end panels of the cabinet all have matching figures.

But I anticipate. The English walnut earmarked for the job had been stored in 1-in. or 3/4-in. boards for the past 20 years at Froxfield. For the bureau’s internal parts, wood that had reached Froxfield 30 or maybe 40 years ago was drawn upon.

The particular oak log that was used came quartersawn, allowing the interesting rays which appear as a silvery splash to be displayed to the best effect. Upton, who made the base with its three drawers and the unusual stretcher rail, declares that this oak was “wonderful stuff”; wonderful, although the sawyers had done their worst and the worms had added theirs.

One edge of the boards, whose thickness tapered from 1/2. in. to 1/4 in., had been completely eaten away. Nonetheless, excellent oak lining was produced. As part of Barnsley’s fining-down policy, the lining measured no more than 1/8 in. thick. This raised peculiar difficulties. Keeping it out of winding during gluing wasn’t easy. Had the oak been a hair’s breadth thinner, traditional joints in all probability could not have been used.

The oak, like the rest of the timber selected for the job, came indoors some months before reaching the planer. This permitted moisture levels to drop as low as possible. George Taylor (at Froxfield since 1937) made the top carcass incorporating the bureau and the bureau’s front flap.

He set about producing the frame and the solid panels with their exotic flame figuring. The flap lay around for some months and gradually there was no denying that the frame rails had moved. “They took this curve on. They were taking on this set,” Taylor recalls.

A blow. No option but to backtrack. The flap was made up again in the solid. Yet again the walnut frame twisted. “Part of the cussedness of the wood,” Taylor comments, with a smile. “You see, the flap is hinged only at one side and there’s nothing to hold it except the frame. And the panels were so strong they pulled the frame out of true.”

Retreat to lamination. A thin marine ply had to be sandwiched up and faced with walnut. So the frame of the flap is, to quote Taylor again, “impervious to all the curious queer creepies you get in wood.”

Now open the flap of the long careful look at the solid panels of the bureau doors. These too have flames that come from single pieces of walnut cut through and opened up like the leaves of a book. From the two fields that face one another come different reflections. One face reflects more light, the other absorbs more light. A negative-positive effect results: Grain on the left-hand panel goes mainly downwards; grain on the right hand panel mainly upwards.

Some scraps and shavings in close-up: On the bureau doors there is a little step between the fielded surface and the curved shoulder, then a further step that goes into the groove of the frame. The stringing of sycamore with ebony diagonals is what Barnsley calls a “dark-light-dark-Iight inlay.”

Its purpose is to outline or contain given areas of work. “Like Picadilly at night,” people used to say. “My mother-in-law as well as my wife expressed criticism of these intermittent inlaid lines,” Barnsley recalls. He listened. His most characteristic signature today is unbroken white stringing.

Barnsley sums up the Jubilee writing cabinet as an explicit “second attempt to move beyond a 1905 design” of his father’s. This, above all, involved general fining down. The sides of chests which used to be 7/8 in. are now 5/8 in. Legs of cabinets are down from 2-1/4 in. to 1-3/4 in.

The dimensions of the stringing were “thought to make the inlays too prominent.” Heeding critical voices, Barnsley says he came to reduce the width of such decorative elements by “50% to 65%, according to the overall dimensions of a piece.”

A lesser signature is the design of Barnsley’s delicate, elegant, and practical handles. On the Jubilee writing cabinet, these have been let in, but they appear to have been carved from the solid. His contemporary handles are placed at the front tops of the drawers.

Earlier they were sited at mid-level. The upper surfaces are gently dished. The inlay of sycamore flows through the swell of the handle. It is formed by dry heat or perhaps a little steam. The grooves are cut with a fine circular saw, except where corners or shapes are involved. Then a scratch-stock is used by hand.

But the midpoint on the bottom drawer is white. Drawer handles, right, are formed from separate pieces of wood mortised into the fronts. The quartersawn drawer sides are about 3/8 in. thick, too thin to be grooved for the solid bottoms. Therefore, a separate drawer slip is glued to their lower edges to house the grooves.

As a rule of thumb, each craftsman makes a piece from start to finish. “It’s yours and you can stand by your work,” says Barnsley. But for bigger orders, everyone in the shop may get involved. The boardroom pieces for Courtaulds were made by Oskar Dawson, Upton, and Taylor.

The Jubilee cabinet is the work of Upton and Taylor. Dawson tooled the ivory knobs: “Nice soft stuff to turn.” Mark Nicholas, the apprentice, cut recesses to receive divisions formed the pigeonholes, and did other odd jobs. Barnsley added finishing touches to the hinges—filing, rounding, and incising delicate lines on them.

Barnsley sums up the past 55 years: “Most of the work from 1924 until 1945 followed closely on Gimson’s and the brothers Ernest and Sidney Barnsley” (his father and uncle).”Developments as from 1945 have mainly taken the form of lightening the work and introducing curves.” Powered tools and lamination made curved work practical and economical.

Slimming down included the elimination of stretchers to brace chair legs, the use of the sturdy gun-stock joint, and the diminution of wood thicknesses.

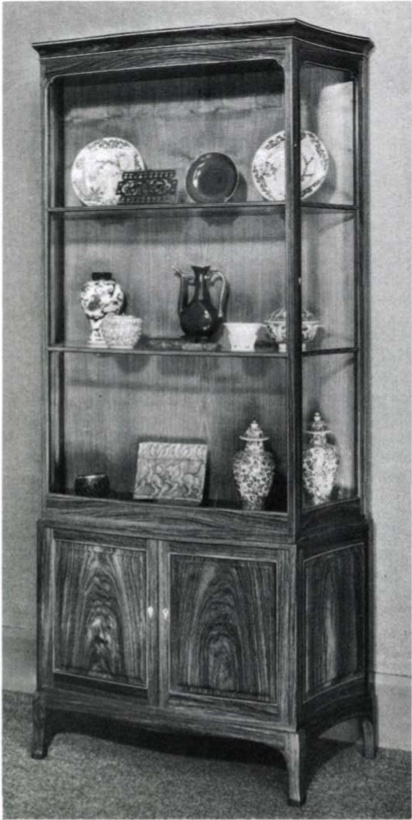

China cabinet (1958) is Indian rosewood with sycamore inlay and measures 78 in. tall and 36 in. wide. The front has a very slight serpentine curve, while the sides are concave—and the glass is curved to match. Note also the carefully shaped feet. |

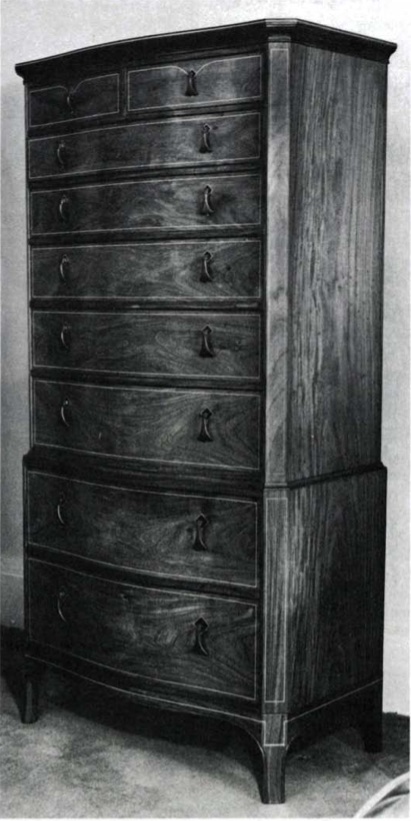

The serpentine front tallboy, in rosewood, was made in three parts—upper chest, lower chest, and base—united by moldings. Wooden buttons, each in its mortise, fasten the base to the lower chest. |

Barnsley, I feel, was never drawn toward the imaginative flights of British innovators such as Ambrose Heal and Gordon Russell. He dismisses much of contemporary furniture design as ephemeral. But words, his or mine, simply offer a faint shadow of the man. The most authentic of Barnsley’s many selves can only be recognized by those exposed to the impact of his work.

Making an Octagon

Limbert Deconstructed

Uncommon Arts & Crafts

Sign up for eletters today and get the latest techniques and how-to from Fine Woodworking, plus special offers.